“The lost giant of American literature”

-The New Yorker

William Melvin Kelley

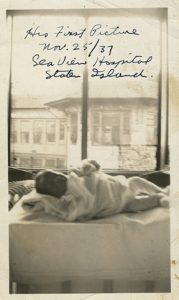

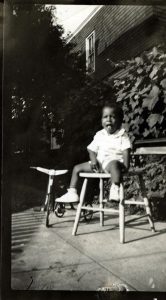

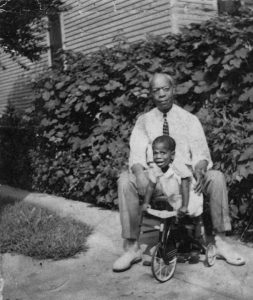

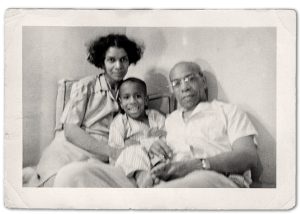

William Melvin Kelley, an African American writer considered part of the Black Arts Movement, known for his experimental prose and satirical explorations of race relations in America was born November 1, 1937, in Seaview Hospital, Staten Island to Narcissa Agatha Kelley (nee Garcia) and William Melvin Kelley Sr. Narcissa, a devout Catholic, suffered from tuberculosis and was advised against continuing her pregnancy. Nevertheless, she persisted, choosing the date of her delivery via cesarean section because it was All Saints Day. The pregnancy and delivery took a toll on her and it was four months before the new family could come home from the hospital.

William Melvin Kelley Sr., a former editor at Harlem’s Amsterdam News attempted to start several newspapers of his own before settling into a career as a New York City civil servant. The Kelleys made their home on the second floor of 4060 Carpenter Avenue, a two-family house owned by Narcissa’s uncle Joe and inhabited by other members of the Garcia family including her mother, Jessie.

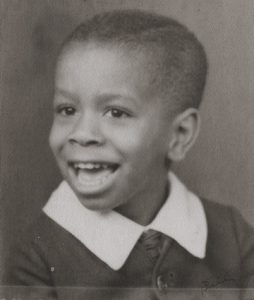

The neighborhood was predominantly Italian; Mr. Kelley’s family were the only family of color on the block. Although he struggled with reading, the Kelley’s only child was perceived to be very bright and was enrolled at the elite Fieldston School in Riverdale. Although Fieldston was integrated since the 1920’s, “Billy” was one of the extremely few African American children. The contrast between his rich, mostly Jewish friends at Fieldston and his working-class Italian friends at home became the wellspring he drew upon in his writing for years to come. “I know rich white people. I know poor white people,” he said in a 2012 interview with Mosaic Magazine. “I know white people.”

Kelley was accepted to Harvard University in 1956 intent on being a civil-rights lawyer, however his life-long struggle with reading prevented success. Always a good storyteller, a skill he attributed to his maternal grandmother Jessie Marin Garcia, he switched to English. He took classes with John Hawkes and Archibald MacLeish, resulting in a short story called “Spring Planting” that won Harvard’s Dana Reed Prize for creative writing and inquiries from literary agents. Eventually Kelley decided he enjoyed writing more than anything else and left Harvard six months short of a degree. His first novel, A Different Drummer was published two years later in 1962.

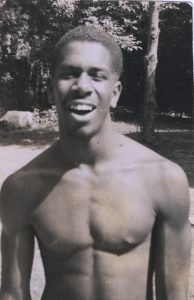

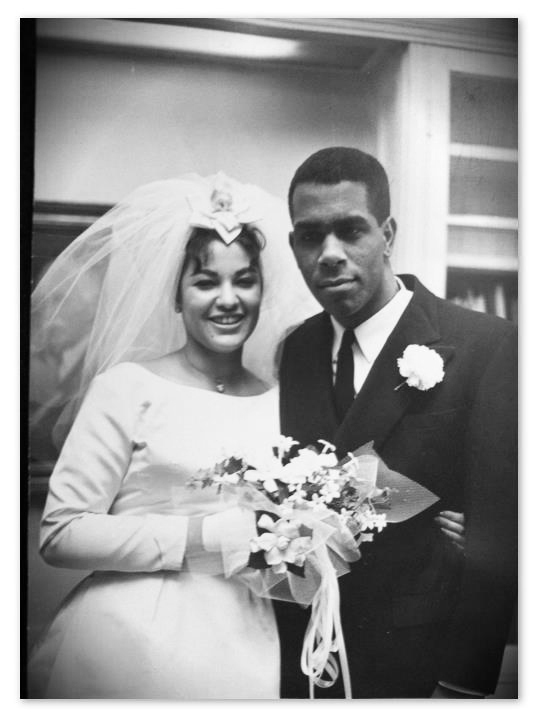

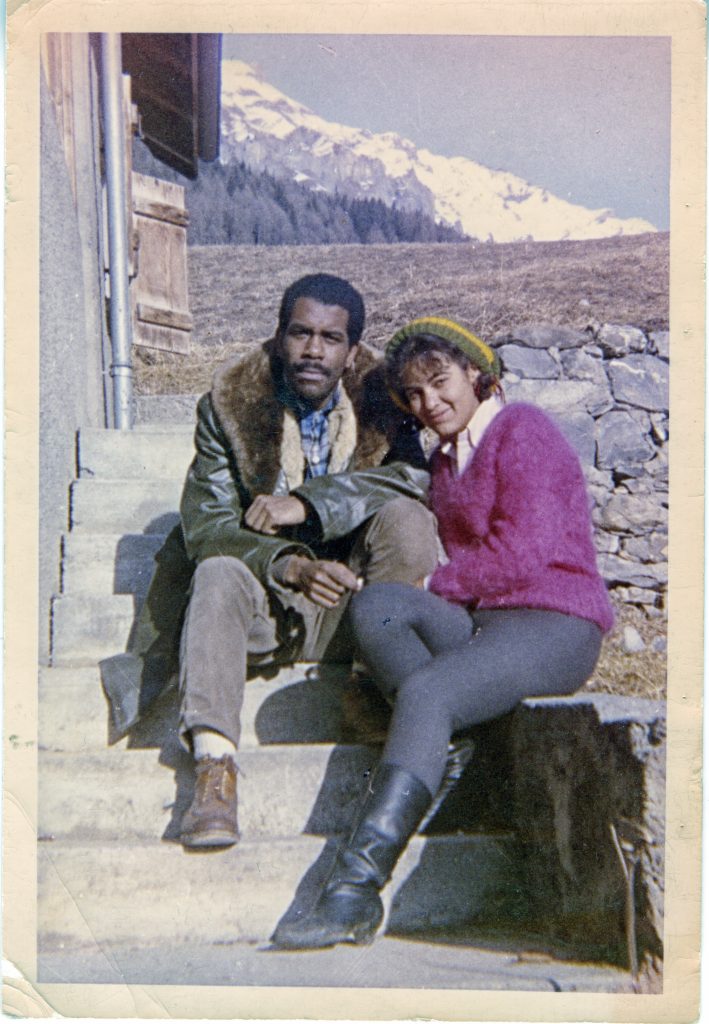

In April of the same year at the Penn Relays (an annual track and field meet hosted by the University of Pennsylvania) Kelley met Karen Gibson, a young woman from Chicago who was studying art at Sarah Lawrence College. While Miss Gibson fell for Kelley immediately (“he was barefoot and when he smiled he had big, white teeth”) Kelley wasn’t convinced she was the one until he took her to meet his grandmother Jessie. “They sat and talked for hours, completely ignoring me” he would say later, “and then I knew she was the one.” They were married on December 15th, a mere eight months later.

Kelley published a book of short stories, Dancers on the Shore in 1964 which debuted many characters—the Bedlows, the Dunfords and the Pierces—who would make appearances in other novels.

His second novel, A Drop of Patience followed in 1965, a pivotal year for Kelley. His first daughter Jessica was born in February, just days before Malcolm X was murdered in front of his wife and children in Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom. A few days later, the Nation of Islam’s Temple No. 7 on West 116th Street was firebombed.

“The whole thing seemed straightforward enough,” Kelley wrote later. “What the Jamaicans call Tribal War. But still I had to look into the faces of the men accused of killing Brother Malcolm, wanted to hear what they had to say about what they had done. I got my agent to secure me an assignment to cover the trial for the Saturday Evening Post, assuring me entrance to the courtroom. So when the trial began in early l966, I had a front row seat at the press table.”

In covering the trial, Kelley became convinced that two of the three men accused of the murder, Norman Butler and Thomas Johnson were being railroaded by the State.

“After the verdict came in, I drove up the West Side highway with tears in my eyes and fear in my heart. The events of the preceding three years had severed the last threads of my faith in the American promise. The rich might usually rip off the poor, politicians might mostly do the will of the industrialists, but at least I had still believed in the independence of the courts. Now I had to give up that idea as well. The Kennedy thing [sic] and now this showed that the State could easily manipulate the courts to serve political purposes. And if the State so badly wanted to convict Butler and Johnson, I knew I wouldn’t have the courage to declare the contrary in the pages of anybody’s magazine, even if they would publish what I had to tell. I wouldn’t assign myself the task of announcing that our little rebellion had failed, that racism had won again for a while. Not with a young wife and a toddler depending on me and all this killing going on. By the time I reached the Bronx, I had decided to depart the Plantation, perhaps permanently.”

It took almost two years for Kelley to move his family from New York to Paris. They lived at 4 Rue Regis, the same building in which author Richard Wright (Native Son, Black Boy) had resided a few years earlier. Kelley’s third novel, dem was published that year. Kirkus Reviews deemed it “more angry” than his earlier work, though acknowledging a “powerful and delicate handling of a heavy theme and an unwieldy plot.” Kelley’s second daughter Cira was born in May 1968, against the backdrop of Paris’ student rebellion. Kelley had intended for their residence in Paris to enable them to learn French and then emigrate to Senegal, but not wanting to move too far away from family that remained in the States, they decided instead on the island of Jamaica. They resided there until 1977.

In 1970 Kelley’s last published novel Dunfords Travels Everywheres explored a mythical foreign country that practiced segregation solely based on whether a person chose a blue or yellow clothing scheme on a particular day. Inspired by James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake Kelley wrote portions of the novel in a dreamlike language, drawing on the cadence and tones of African American “patois” combined with standard English.

Upon returning to America in 1977 Mr. Kelley and his family settled in Harlem. Through a connection with his mentor, American novelist and academic Joseph Papaleo (Italian Stories) Kelley began teaching at Sarah Lawrence College in 1989.

Although Kelley did not publish another full-length novel after Dunfords…, he wrote many essays and short stories, appearing in magazines such as The New Yorker, Playboy, and Harper’s. His short stories also appear in numerous anthologies and academic textbooks. Kelley has received numerous awards during the course of his career such as the Rosenthal Foundation Award and the John Hay Whitney Foundation Award (1963) for A Different Drummer. His short story collection, Dancers on the Shore, won the Transatlantic Review Award (1964) and his last Dunfords… received honors from the Black Academy of Arts and Letters. As a culmination he was the recipient of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2008.

In addition to writing, Kelley was an avid photographer and videographer. He took several thousand photographs chronicling his life in Paris and Jamaica and in 1988 he collaborated on a video with mixed-media technology artist Stephen Bull called Excavating Harlem. The 28-minute short won a small prize which Kelley used to buy a video camera. From 1989 until about 1992, he kept a video diary as a way to capture the beauty of Harlem he saw around him and felt he could not describe in words. The resulting video, some of it damaged by years of storage, was collected and edited by Benjamin Oren Abrams over the course of two years, into another short called The Beauty That I Saw. The film debuted in the 2015 Harlem International Film Festival where it won a Harlem Spotlight Award.

Kelley was a man of deep and quiet spirituality. He followed—as closely as he could without benefit of an official conversion—the Judaic faith, calling himself a Child of Moses. He often said that as a poor reader, there were only two books in his life that he had read end-to-end; James Joyce’ Ulysses, and the Bible. Mr. Kelley also had a reverence for cannabis, which is worth mentioning as he was wont to inform anyone that he smoked “The Blessed,” whether they asked or not.

Mr. Kelley lived in the Dunbar apartments in Harlem, a complex that had been constructed in 1926 as an experiment in housing reform to alleviate the housing shortage in Harlem and to provide housing for African Americans. Notable African Americans who had lived in the Dunbar prior to Kelley include W. E. B. DuBois, Paul Robeson, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Countee Cullen and the explorer Mathew Henson.

For the last 18 years of his life, three days a week, Kelley was a dialysis patient at Mount Sinai Kidney Center at East River Plaza after bladder cancer caused his kidneys to fail. In 2009 his right leg was amputated due to circulatory issues. Despite these serious health issues, Kelley continued to teach Creative Writing at Sarah Lawrence College twice a week.

In the winter of 2016, Kelley, or “Duke” as he was known in Harlem,

had finished teaching the winter semester at SLC and had been very excited about his latest class of new writers. He died on Wednesday, February 1, 2017, at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. He was 79.